I often, sometimes willingly and others without noticing, find myself sucked into moments of deep serendipity on the Internet (YouTube, in my case), falling into what seems to be a universally appealing rabbit hole in that platform: hyper-productivity tools. I’m thinking of tools like Obsidian, Logseq, Notion, and others that promise the perfect environment to manage information and enhance productivity.

In this landscape, Artificial Intelligence apps inevitably appear as the ultimate productivity-boosting star, cleverly packaging foundation models in sleek user interfaces that make them look like bespoke solutions to any area of our lives. And while I’m no neo-luddite (I actively use AI and knowledge management apps in my daily workflows – Capacities is my tool of choice), my first-hand experience has made me acutely aware that some areas can’t be “hyper-productive”. The most important of these is the act of thinking itself.

This morning, my YouTube binge highlighted my concern when I encountered a productivity vlogger who claimed it would soon take longer to read and comprehend information than create it. Beyond the statement, what called my attention was the solution. She proposed using AI to “improve the quality of our inputs”, using tools like Elicit for selecting research papers, Notebook ML for summarisation and analysis, and Claude for outlining and making everything actionable.

I have experimented with such workflows myself, and while they can be powerful for sounding the field and exploring ideas, I’ve found they’ve never truly replaced, not even inspired, my deep thinking process.

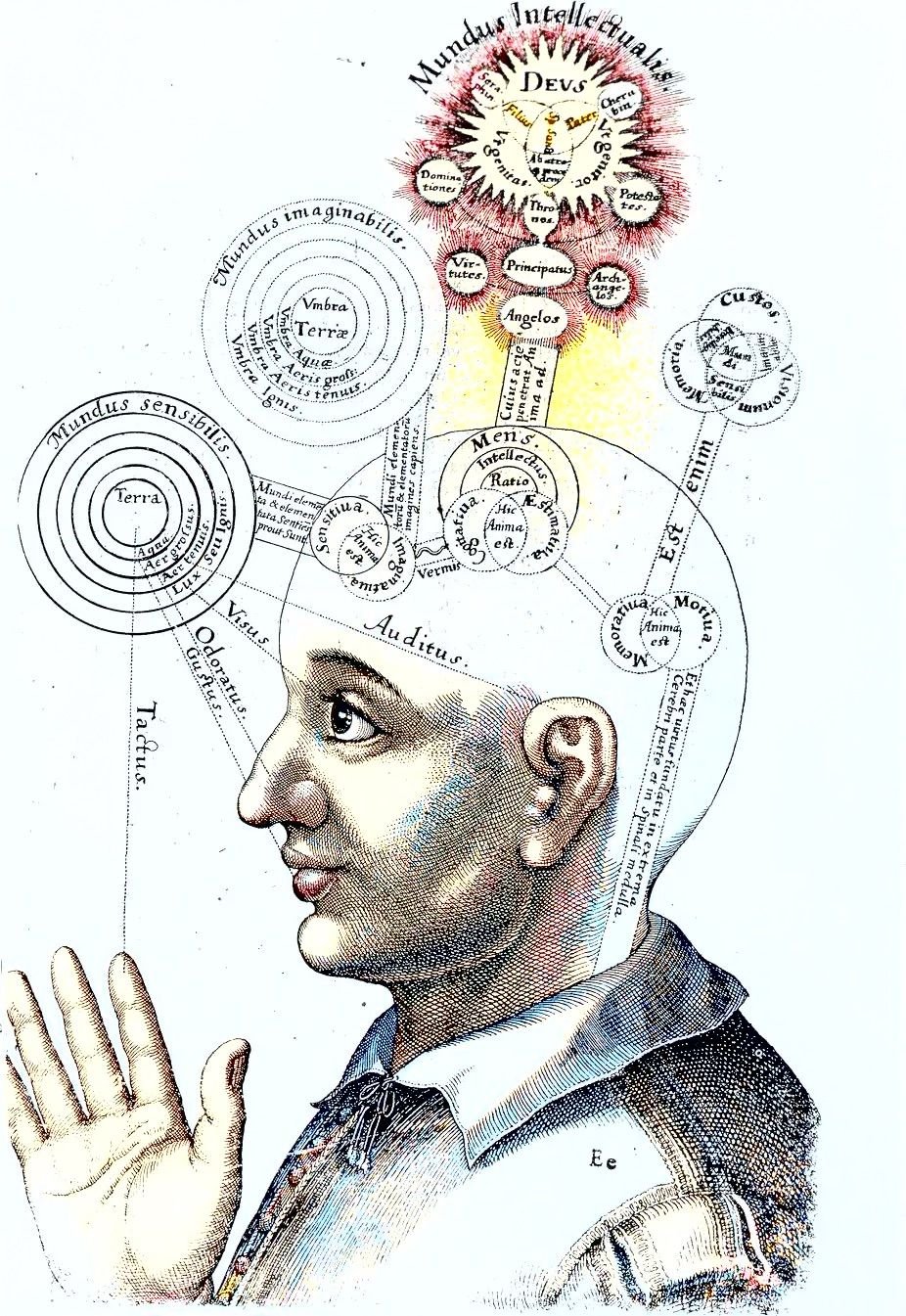

The reason is basic in nature: genuine thinking and sense-making take place within our bodies. Our physical selves need proliferous and bloated data to grasp subtle ideas. We need rhetoric to weigh arguments, and metaphors to connect concepts and examine our positions. We need the world’s richness and messiness to break down its components into digestible nutrients instead of ingesting highly processed, loosely compressed and statistically pixelated ideas. It’s in the moments of wrestling with complexity that actual thinking happens.

This perspective isn’t merely personal speculation. Daniel Kahneman, in his seminal work “Thinking, Fast and Slow“, elaborates on this process in detail. Even within the YouTube productivity community, or rabbit holes, this truth is recognised. Many creators express frustration at spending countless hours perfecting their workflows and customising tools, only to realise that once all data is parsed, filtered, and organised, only then, the real work begins.

The critical moment comes when we must shift from organisation mode (searching and filtering data) to deep thinking mode (interpreting and producing new knowledge), which in Kahneman’s model roughly extrapolates to switching from system 1 to system 2. This transition requires us to dive into the collected information and let it permeate our bodies, embracing all the singularities of our collected texts, images, sounds, and videos – experiencing them as objects rather than mere data points, and experiencing us as biological organisms rather than walking CPUs. Deep thinking demands a different skill set than scanning texts and prompting for results, which neither knowledge management tools nor AI can provide.

In essence, while modern tools can undoubtedly help us organise our thoughts, they cannot think on our behalf. And if they cannot think on our behalf, we must then forge our own opinions, which requires us to dive deeper into the complexities of texts and not only AI-generated summaries distributed in pristine and sleekly structured blocks of notes. The path to deep thinking requires us to embrace the mess and let our bodies break down information into our digestive system of ideas, where the brain plays a chief role, but not without the help of other organs. Perhaps it’s time we acknowledged that true productivity in thinking isn’t just about speed or efficiency but, most importantly, about finding the time, space and rhythm our bodies need to produce valuable insights.